Style is where our ability bumps up against our ambition, so technically, we *always* have a style. That means too, that as our abilities grow and ambitions change, our style is always evolving.

There's an interesting interview of Bono in which he says that the "U2" sound that everyone was trying to copy in the 80s was just them trying to sound like other bands. He says they weren't that great as musicians when they started and their sound is just "what came out"; it was their own interpretation of what was going on in the rock culture and it was unique to them because of their then-limited abilities, personal experiences, and ambitions as a band.

We tend to look for inspiration from other artists who inspire us and we sometimes start simply by copying their work to get a feel for their lines, their proportions, or their design. Soon, we might try our own compositions and will perhaps lean on the well-known artist's design to carry ours through as we gain confidence and start to hear our own voice. As our technical skills grow, so does our ambition which means our style becomes more unique to us and our way of thinking about how our work should look and what it should "say".

My artistic youth was bathed in a traditional stew of National Geographic, Audubon, and Rockwell which piqued my interest in the natural world and "realism". When I was in high school, though, I was introduced to the work of Aubrey Beardsley, Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Alphonse Mucha and with all of their glorious design and technical drawing skills and lovely weirdness -- and right there is where the mashup deliciousness started in my brain. It's with block prints of Hokusai that I began to understand elegant design; with Mucha the importance of line weight; Beardsley's magical worlds dancing in simple penwork was both heavy and light, a perfection of contrasts and textures.

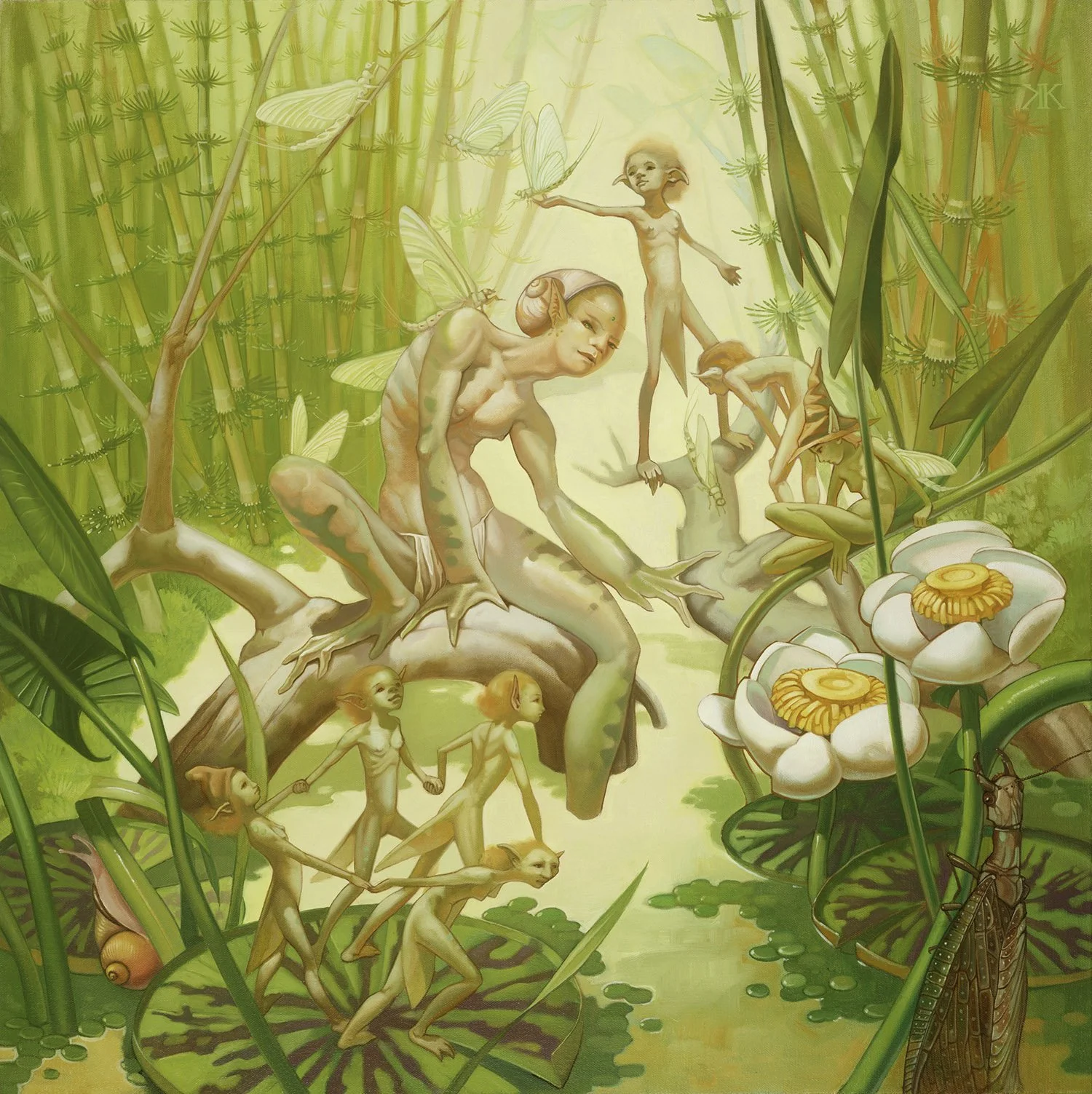

Later, as a young adult, I discovered the trippy work of Brian Froud, the austere colored pencil insects of Walter Linsenmaier, the wildness of Frank Frazetta's world, the mathematical and hypnotic Escher, the lusciousness of Rachel Ruysch's flowers, among others and they inspired me a great deal even though I was doing science and educational illustration. In grad school, while still growing and deepening my artistic practice, I discovered the bodily paint quality of Francis Bacon and Jenny Saville, the fevered visions of Bosch, and many others whose work affected mine in profound ways that I'm only just beginning to understand.

So far I've only really addressed facture, or how one's "hand" shows up in a work or how an artist applies wet or dry media to a surface and what that looks like. I've been talking about behavior with media. But the choice of what to paint to create presence in a work ~ the subject matter and content ~ deals with more with the *why* one makes art. It's the worldview of the artist that is married to the facture and this is the strongest manifestation of an artist's work and is what we think of as style.

Can you imagine Francis Bacon's ideas delivered via anything other than the slithery, visceral paint marking his canvases? Can you imagine Escher's drawings created in anything less exact than the ones he made? The facture or the delivery of the idea via the medium and how it was handled says SO much about what the work of art means. Yes, the subject matter is there to clue us in on what the story's about but the handling of the paint, the light, the color, the marks, tells us so much more about the work's content and how we should read it.

We develop a style slowly, combining our interests, our influences, our ideas and worldview, our ambition, and we chew on it for a while until it really coalesces into the thing that best represents our work.

Some say nothing is new except how we recombine it. That would suggest that there are an infinite number of new works still to be made in utterly new styles.