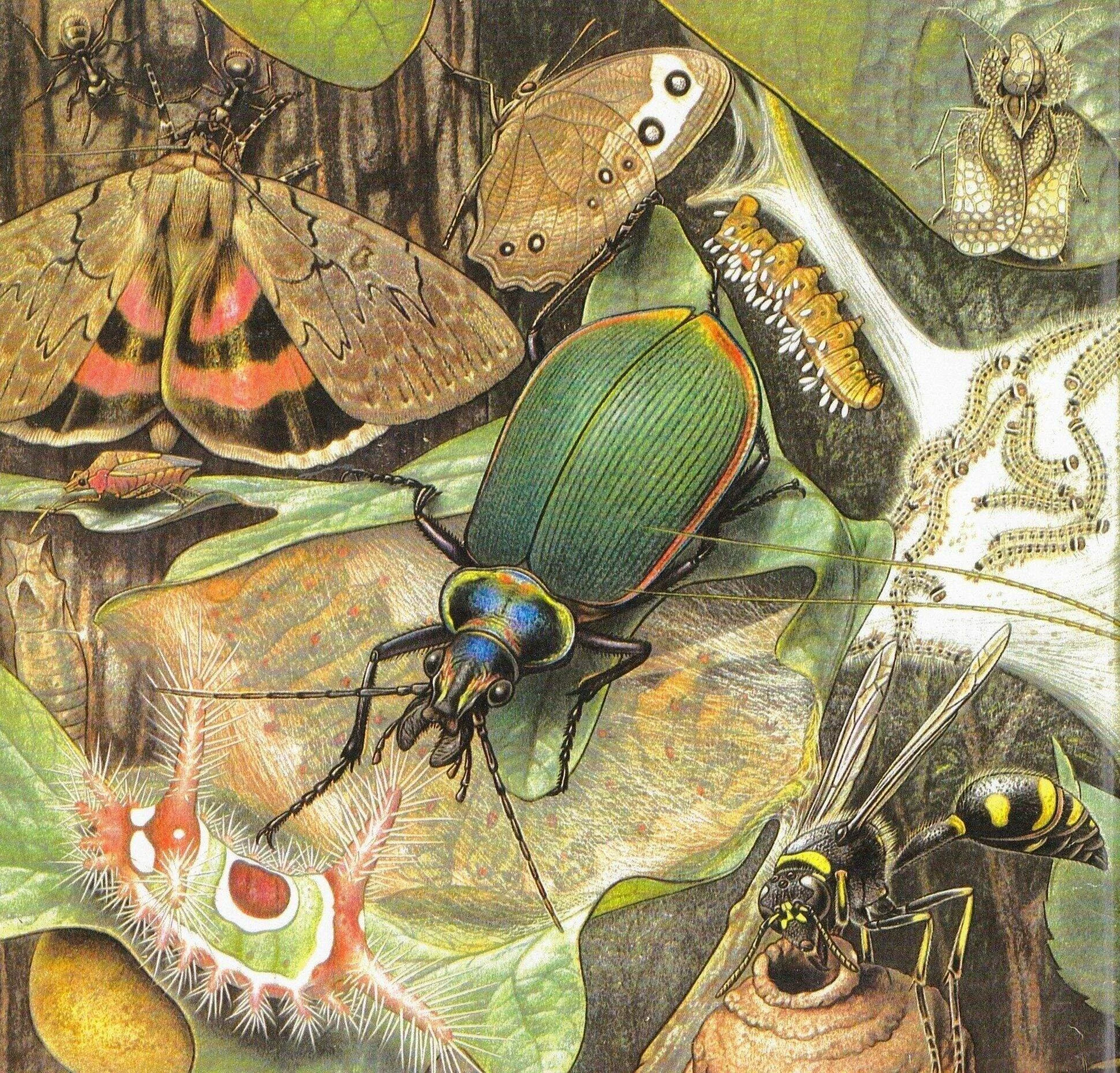

In 1995, Franklin Watts published the Animal Skeletons book which I had immense joy in illustrating. I mean, who wouldn’t luuuurrv painting and drawing skeletons and bugs and hardshelled animals, etc?!

When I started looking at the art direction and started thinking about what reference I’d need for the illustrations, I remembered that my old high school biology teacher, Mr. Larry Strait, had a rather nice collection of proper animal skeleton mounts from a biological supply company. I asked him if I could borrow them so I could make drawings for a book and he said yes! I don’t know what the heckin heck he was thinking, loaning this fragile stuff out to a 25 year old, but soon enough I was driving away from my old high school with the skeletons of a cat, a turtle, a chicken, a frog, and a shark in a 2’ tank of formaldehyde.

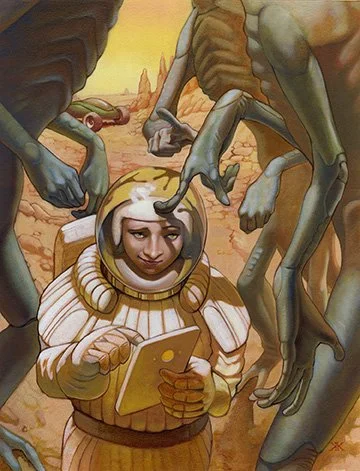

A local college had a wonderful museum collection which proved to be an invaluable resource of information for several of the lizard and fish skeletons, which I drew on site and photographed. The art direction got a bit more challenging when I was tasked to create an an image that showed the development of the skull of a flounder, explaining how the one eye migrates to the other side of the fish so it can lay flat in the sand with both eyes “up”. I couldn’t find clear reference for this, so I had a crazy idea that I could just extrapolate what the “middle phase” of the eye’s movement would look like. I first bought a flounder head and painted it from life. And then I boiled down the fish head to release the flesh from the bones and then reassembled them so I could observe and draw.

Voila— A regular fish skull is on the far left, the flounder on the right, and the extrapolated skull development in the middle. The eye moves to the other side when the flounder is still a small fry.

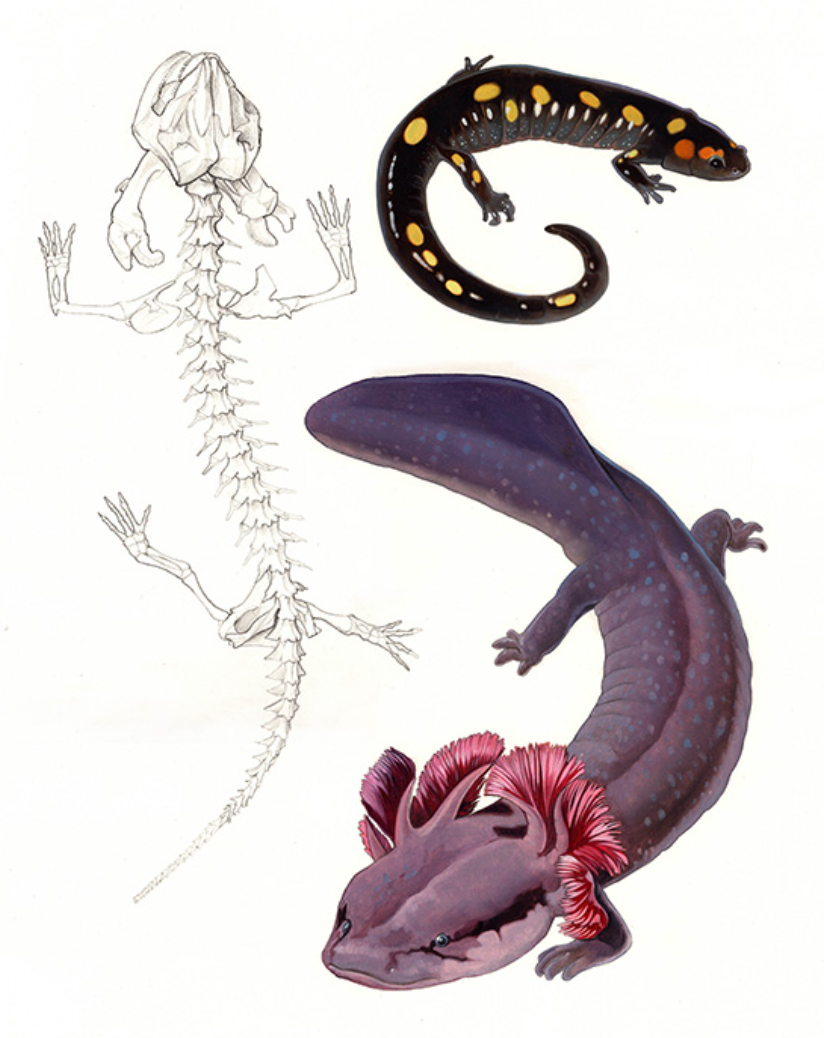

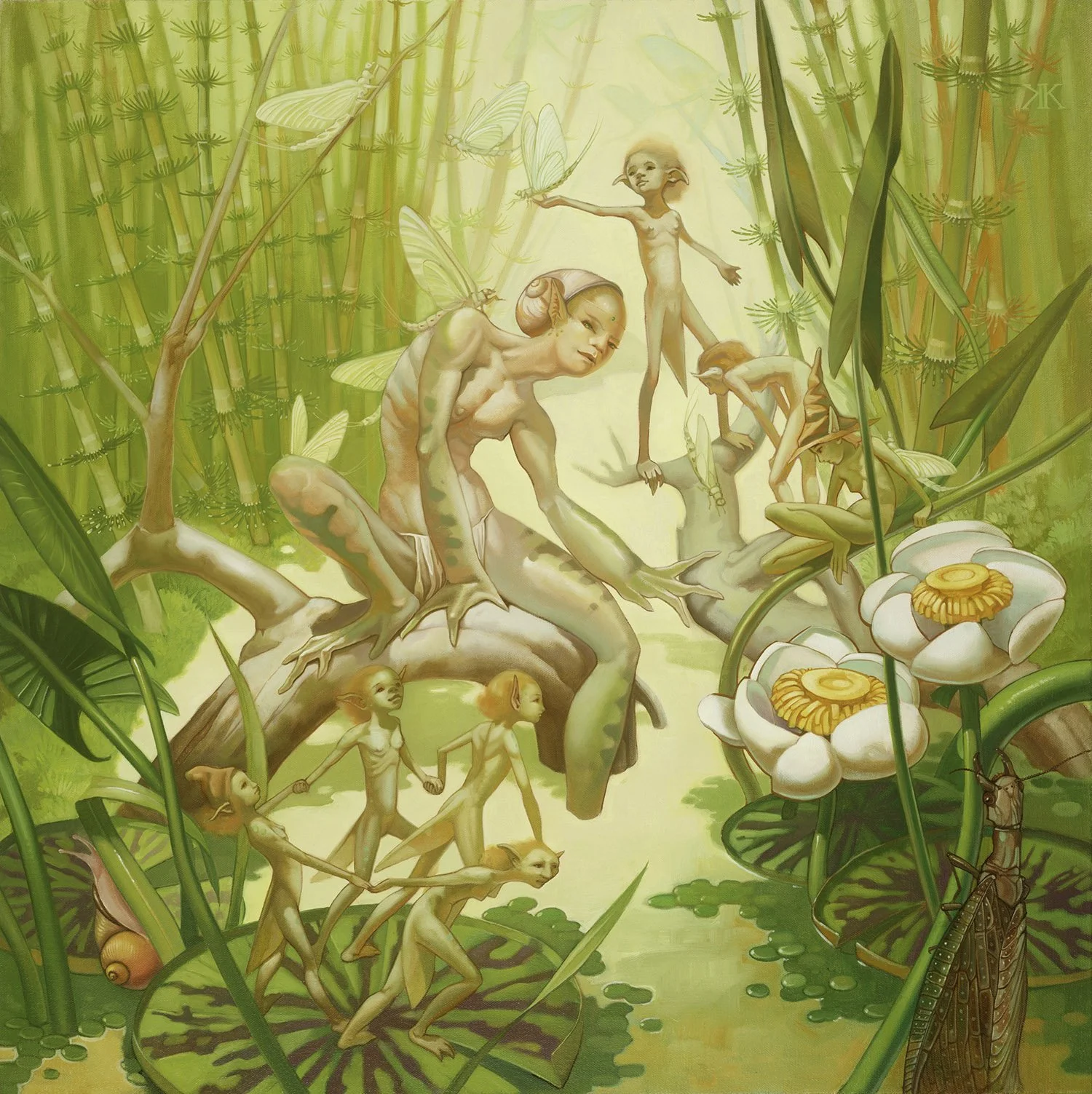

Animal Skeletons book interior spread of a colorful axolotl and an amphibian skeleton.

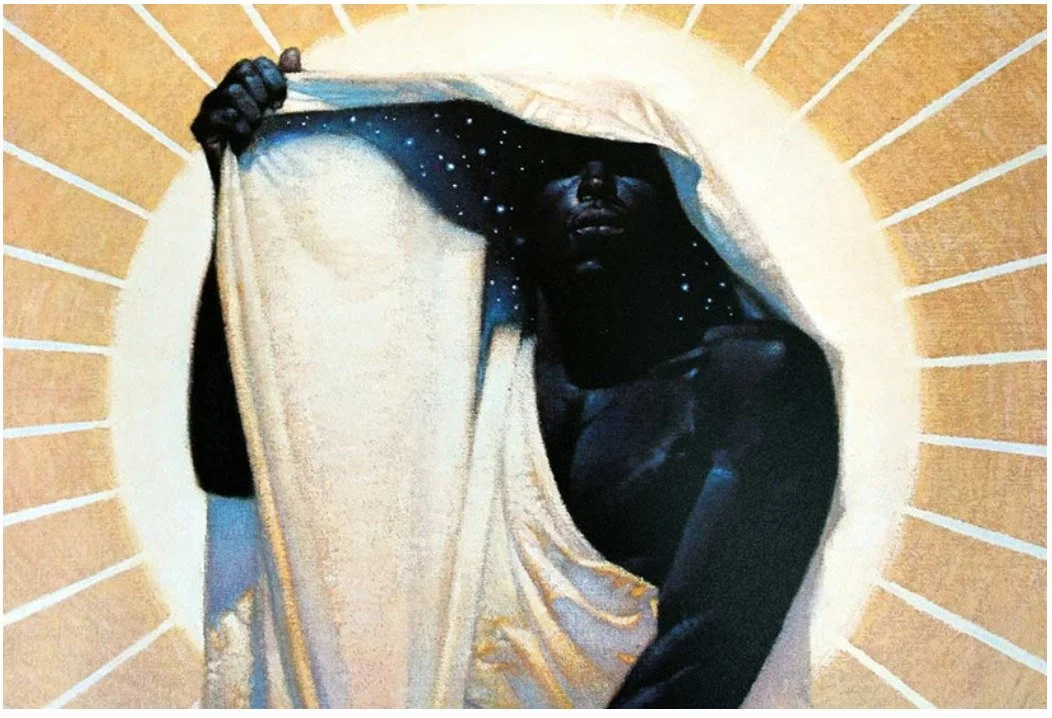

A half-page image showing the tiny ear bones.

In high school I thought I’d like to pursue medical illustration, but it would have been a too-narrow focus and like everything else, the field was rapidly shifting into digital illustration (and now animation). It was fun to be able to do a few half-page illos to flex my interest a bit.

I’d kept the mounts for a few years, safe and sound, and when my former teacher retired, he requested I return them to the biology lab, which I did. Such fun memories are contained in books— and not just for the reader, but for the artist (and presumably the author) making the work. Thanks, Mr. Strait, for all your help!